?What is synesthesia and what's it like to have it

Synesthetes can taste sounds, smell colors or see scents, and research proves these people experience reality differently.

I know that the number four is yellow, but I have a friend who insists four is red.

Some synesthetes feel music on certain parts of their bodies. (Photo: Kristen Stacy/flickr)

She also says four has a motherly personality, but my four has no personality — none of my numbers do. But all of my numbers have colors, and so do my letters, days and months.

My friend and I both have synesthesia, a perceptual condition in which the stimulation of one sense triggers an automatic, involuntary experience in another sense.

Synesthesia can occur between just about any combination of senses or cognitive pathways.

Synesthetes — or people who have synesthesia — may see sounds, taste words or feel a sensation on their skin when they smell certain scents. They may also see abstract concepts like time projected in the space around them, like the image on the right.

Synesthetes — or people who have synesthesia — may see sounds, taste words or feel a sensation on their skin when they smell certain scents. They may also see abstract concepts like time projected in the space around them, like the image on the right.

Many synesthetes experience more than one form of the condition. For example, my friend and I both have grapheme-color synesthesia — numbers and letters trigger a color experience, even though my experience differs from hers.

Because her numbers have personalities, she also has a form of synesthesia known as ordinal-linguistic personification.

Scientists used to think synesthesia was quite rare, but they now think up to 4 percent of the population has some form of the condition.

What's it like?

David Eagleman, a neuroscientist and director of the Laboratory for Perception and Action at the Baylor College of Medicine, isn't a synesthete, but he often uses this analogy to explain the phenomenon.

When you see this photo, you likely think "President Barack Obama" even though those words aren't written anywhere on the picture. Your brain automatically and involuntarily makes that connection, much like my brain makes a connection between the number four and the color yellow.

"It's not the same as a hallucination," Eagleman explains in the documentary "Red Mondays and Gemstone Jalapenos." "It's not actually interfering with their ability to see, so in that same way, you could picture a giant orange pumpkin sitting in front of you, but that doesn't prevent you from seeing through that and past that."

Synesthesia is a sensory phenomenon that's unrelated to memory, so if you're not a synesthete, you could teach yourself to associate a color with a certain number for example, but your brain wouldn't respond the same way a synesthete's would.

For instance, someone without grapheme-color synesthesia would have a more difficult time picking out the black twos from the black fives in the image on the right.

For instance, someone without grapheme-color synesthesia would have a more difficult time picking out the black twos from the black fives in the image on the right.

However, if your numbers have colors, you'll see the triangle of twos almost instantly.

But this task may be even easier for some grapheme-color synesthetes.

Daniel Smilek, a psychology professor at the University of Waterloo, has identified two groups of synesthetes among those who associate colors with letters and numbers. There are projectors, those whose colors fill the printed letter in front of them, and associators who see the colors in their mind's eye, like I do.

What causes it?

About 40 percent of synesthetes have a first-degree relative with synesthesia, and many synesthetes recall having synesthesia as long as they can remember.

"I was definitely playing with it when I was 5 or 6 years old because I remember raiding my parents' record cabinet, searching for records that I liked to listen to for colors," said Sean Day, a synesthete who associates colors with both sounds and tastes.

A 2018 study conducted by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics and the University of Cambridge analyzed DNA samples from several families who have multiple generations of synesthetes. They concluded that while the families differed in DNA variations, there was one commonality. There was an enhancement of genes involved in cell migration and axonogenesis – a process that enables brain cells to wire up to their correct partners.

"This research is revealing how genetic variation can modify our sensory experiences, potentially via altered connectivity in the brain," Professor Simon Baron-Cohen stated in the study. "Synesthesia is a clear example of neurodiversity which we should respect and celebrate."

Other experts believe that everyone may be born with the ability to experience synesthesia.

Daphne Maurer, a psychologist at McMaster University, has speculated that all of us may be born with the neural connections that allow synesthesia, but that most of us lose those connections as we grow.

Eagleman acknowledges there may be synesthetic correspondences in the brains of non-synesthetes, but that people are unaware of them until they're teased out.

He points to something called the bouba/kiki effect as an example. When asked to choose which of two shapes on the right is named "bouba" and which is "kiki," most people choose kiki for the angular shape and bouba for the rounded one.

He points to something called the bouba/kiki effect as an example. When asked to choose which of two shapes on the right is named "bouba" and which is "kiki," most people choose kiki for the angular shape and bouba for the rounded one.

Research also shows that people are likely to say that louder tones are brighter than soft ones and that darker liquids smell stronger than lighter ones.

In his book, "Wednesday Is Indigo Blue," Eagleman says these examples prove that these analogies are actually "pre-existing relationships."

"In this way, synesthetic associations our ancestors established long ago grew into the more abstract expressions we know today — and this is why metaphors make sense," he writes.

However, synesthesia differs from these examples in that the sensory experience triggered is automatic and unlearned, making it different from metaphorical thinking.

"It's a genuine phenomenon, and people who have it are actually experiencing the world differently," Eagleman said.

How is it tested?

Consistency is one of the best ways to test for synesthesia.

"If you tell me that your letter 'J' is a very particular shade of powder blue … I can test you on that and have you identify exactly the shade that best matches," Eagleman said. "If you're just being poetic or metaphorical or making something up, then you can't capture those colors again. But if you're really synesthetic, then you'll be able to pick exactly those colors out years later."

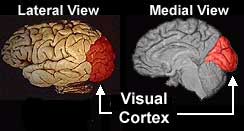

Researchers also look at synesthetes' brains.  Using positron-emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging, they've found that people who report seeing colors in music, for example, have increased activation in the visual areas of the brain in response to sound.

Using positron-emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging, they've found that people who report seeing colors in music, for example, have increased activation in the visual areas of the brain in response to sound.

Using positron-emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging, they've found that people who report seeing colors in music, for example, have increased activation in the visual areas of the brain in response to sound.

Using positron-emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging, they've found that people who report seeing colors in music, for example, have increased activation in the visual areas of the brain in response to sound.

Pictured right are the regions of the brain that are thought to be cross-activated in grapheme-color synesthesia.

The pros and cons

Some synesthetes say their condition can be uncomfortable at times. For example, seeing words printed in the wrong color can be strange, or certain names may taste bad to a synesthete. Others report suffering sensory overload or feeling embarrassed at a young age when they describe experiences they didn't know were atypical.

However, most synesthetes think of their abilities as a gift and wouldn't want to lose them.

"You've experienced extremely unpleasant odors," Day points out. "Do you want to permanently lose your sense of smell?"

There may also be some benefits to being a synesthete, such as an ability to discern similar colors and easily memorize information. For example, I might not remember a digit in a phone number, but I'll have an impression of green and therefore know the mystery number is six. (Some of my numbers are pictured right, as depicted by the Synesthesia Battery.)

For example, I might not remember a digit in a phone number, but I'll have an impression of green and therefore know the mystery number is six. (Some of my numbers are pictured right, as depicted by the Synesthesia Battery.)

For example, I might not remember a digit in a phone number, but I'll have an impression of green and therefore know the mystery number is six. (Some of my numbers are pictured right, as depicted by the Synesthesia Battery.)

For example, I might not remember a digit in a phone number, but I'll have an impression of green and therefore know the mystery number is six. (Some of my numbers are pictured right, as depicted by the Synesthesia Battery.)

In 2005, Daniel Tammet set the European record for pi memorization by memorizing 22,514 digits in five hours. He attributed the feat to his ability to see numbers with color, texture and sound.

There's also evidence that synesthesia may enhance creativity. A 2004 study at the University of California had a group of students take the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. The synesthetes who took the test scored more than twice as high in every category.

In some instances, the neurological condition has even led to unique job opportunities. Some car manufacturers, for example, are hiring synesthetes to help designers create cars that are more pleasing to potential drivers.

And synesthetes keep good company. The list of known synesthetes is long and includes Vladimir Nabokov, Vincent Van Gogh, Marilyn Monroe, Billy Joel and Mary J. Blige.

Musician Pharrell Williams associates music with colors and says he can't imagine life without this "gift."

"If it was taken from me suddenly I'm not sure that I could make music," he told Psychology Today. "I wouldn't be able to keep up with it. I wouldn't have a measure to understand."

|  | |

What is synesthesia?Synesthesia is a condition in which one sense (for example, hearing) is simultaneously perceived as if by one or more additional senses such as sight. Another form of synesthesia joins objects such as letters, shapes, numbers or people's names with a sensory perception such as smell, color or flavor. The word synesthesia comes from two Greek words, syn (together) and aisthesis (perception). Therefore, synesthesia literally means "joined perception."Synesthetic perceptions are specific to each person. Different people with synesthesia almost always disagree on their perceptions. In other words, if one synesthete thinks that the letter "q" is colored blue, another synesthete might see "q" as orange.  DiagnosisAlthough there is no officially established method of diagnosing synesthesia, some guidelines have been developed by Richard Cytowic, MD, a leading synesthesia researcher. Not everyone agrees on these standards, but they provide a starting point for diagnosis. According to Cytowic, synesthetic perceptions are:

Who has it?

Famous PeopleSome celebrated people who may have had synesthesia include:

The Biological Basis of SynesthesiaSome scientists believe that synesthesia results from "crossed-wiring" in the brain. They hypothesize that in synesthetes, neurons and synapses that are "supposed" to be contained within one sensory system cross to another sensory system. It is unclear why this might happen but some researchers believe that these crossed connections are present in everyone at birth, and only later are the connections refined. In some studies, infants respond to sensory stimuli in a way that researchers think may involve synesthetic perceptions. It is hypothesized by these researchers that many children have crossed connections and later lose them. Adult synesthetes may have simply retained these crossed connections. It is unclear which parts of the brain are involved in synesthesia. Richard Cytowic's research has led him to believe that the limbic system is primarily responsible for synesthetic experiences. The limbic system includes several brain structures primarily responsible for regulating our emotional responses. Other research, however, has shown significant activity in the cerebral cortex during synesthetic experiences. In fact, studies have shown a particularly interesting effect in the cortex: colored-hearing synesthetes have been shown to display activity in several areas of the visual cortex when they hear certain words. In particular, areas of the visual cortex associated with processing color are activated when the synesthetes hear words. Non-synesthetes do not show activity in these areas, even when asked to imagine colors or to associate certain colors with certain words. It is unclear which parts of the brain are involved in synesthesia. Richard Cytowic's research has led him to believe that the limbic system is primarily responsible for synesthetic experiences. The limbic system includes several brain structures primarily responsible for regulating our emotional responses. Other research, however, has shown significant activity in the cerebral cortex during synesthetic experiences. In fact, studies have shown a particularly interesting effect in the cortex: colored-hearing synesthetes have been shown to display activity in several areas of the visual cortex when they hear certain words. In particular, areas of the visual cortex associated with processing color are activated when the synesthetes hear words. Non-synesthetes do not show activity in these areas, even when asked to imagine colors or to associate certain colors with certain words.Synesthesia and the Study of ConsciousnessMany researchers are interested in synesthesia because it may reveal something about human consciousness. One of the biggest mysteries in the study of consciousness is what is called the "binding problem." No one knows how we bind all of our perceptions together into one complete whole. For example, when you hold a flower, you see the colors, you see its shape, you smell its scent, and you feel its texture. Your brain manages to bind all of these perceptions together into one concept of a flower. Synesthetes might have additional perceptions that add to their concept of a flower. Studying these perceptions may someday help us understand how we perceive our world. |

Hear IT! Hear IT! | Synesthesia | Limbic |

| Synesthesia Experiment

|

Involuntary: synesthetes do not actively think about their perceptions; they just happen.

Involuntary: synesthetes do not actively think about their perceptions; they just happen. Women: in the U.S., studies show that three times as many women as men have synesthesia; in the U.K., eight times as many women have been reported to have it. The reason for this difference is not known.

Women: in the U.S., studies show that three times as many women as men have synesthesia; in the U.K., eight times as many women have been reported to have it. The reason for this difference is not known. Vasily Kandinsky (painter, 1866-1944)

Vasily Kandinsky (painter, 1866-1944)

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق